Just some light material for your evening reading...!

Today I have been quite preoccupied with the vote that was happening today, which ultimately passed, to approve plans to restrict increases in benefits to 1% per year. Why's that such a big deal? Because benefits have historically risen in line with inflation. While I don't think any of my readers are the type of people who begrudge the unemployed Jobseekers' Allowance, it's worth noting that, despite the way the government and media present it, most people in receipt of benefits are in fact employed in some capacity. Cuts affect those who receive:

- Jobseeker's Allowance

- Employment and Support Allowance

- Income Support

- Elements of housing benefit

- Maternity allowance

- Sick Pay, Maternity Pay, Paternity Pay, Adoption Pay

- Couple and lone parent elements of working tax credits and the child element of the child tax credit

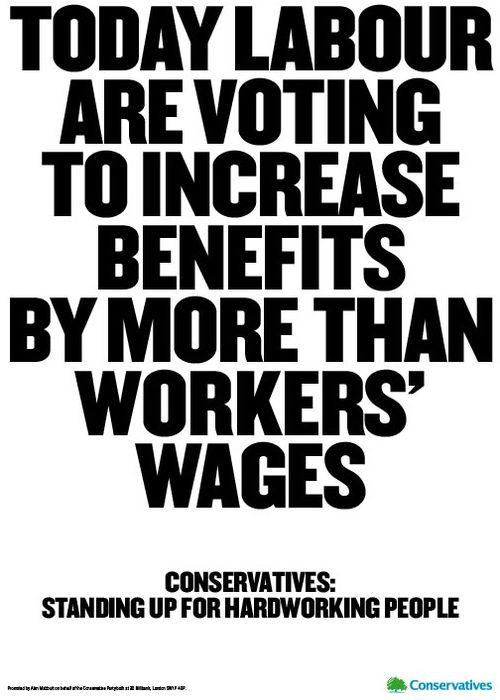

The Conservatives have framed the rhetoric of this debate around a discourse of deserving vs undeserving poor. They spend a lot of energy talking about "scroungers". It has been consistently demonstrated by studies that while of course there is benefit fraud, far more money - millions and millions more! - is wasted every year in administrative errors with regards to benefit than is lost in benefit fraud. The government also helpfully ignores the fact that the recession is what has put a large proportion of people on benefits, and that, as we now risk going into a triple dip recession, austerity measures can be quite confidently said to not work as a way of moving out of financial crisis. Furthermore, as this excellent article points out, the government assists big business by supplementing the low wages of the workers at companies like Starbucks by paying them housing benefit and working tax credits, because the national minimum wage is not equal to what is termed a living wage. I'll say it again: most benefits go to the employed.

This, of course, isn't even touching on the issue of people who cannot work due to ill health, disabilities etc. I believe that here in the UK the economically disadvantaged are still in a better position than they are in the US - free healthcare, for instance, although the Tories are doing their best to carve that up - but I have been troubled by the rise of right-wing rhetoric that echoes the kind of ultra-conservative soundbites we're used to hearing from across the pond. Pull yourself up by your bootstraps, even if you don't have boots, all that.

I've been tweeting quite a bit about this today. People have also been tweeting heavily over the last couple of days under the hashtag#TransDocFail, which records the experience of trans people across the world with the medical establishment. I haven't contributed to this discussion apart from by retweeting a couple of things, because this particular hashtag seems to me to be a place where trans people's voices are meant to be heard, and chiming in to me seems to be trying to muscle in on stories of very personal and distressing experiences of prejudice and neglect. They don't need me to filter them. But in reflecting on events today, I have seen some parallels. Here's an example.

Westminster Council proposed that obese and otherwise 'unhealthy' people could have their benefits docked if they failed to carry out GP-prescribed exercise. Their rationale behind this is that Britain's obesity epidemic is raising the rate of diabetes II, heart disease and various other conditions that cost the NHS a great deal of money. I don't dispute this, and I think that many people (myself included!) would be much healthier if they did regular exercise. However, this blackmailing of economically vulnerable people is pretty disgusting - it says "you deserve help only if you change your body in ways these authority figures approve of." This, of course, is the regular experience of trans people when seeking medical help. It assumes that marginalised people can't possibly have any idea of what is best for them and their bodies. It also neglects the fact that, in the case of overweight people on benefits, reasons for obesity don't usually come from laziness - they are closely tied to poverty, and to cultures of poverty involving lack of education (that means people have little understanding of nutrition, or aboutemotionally healthy eating), long working hours for low wages (that may make exercising difficult or impossible), lack of access to cheap healthy food (for instance: being able to drive to a supermarket if you live on an inner city estate can be pretty impossible; your local small Iceland meanwhile will stock you up on cheap frozen food for very little). But the government refuses to see these well documented causes, preferring a simple, splashy tagline about tackling scroungers. Trans people, meanwhile, are asked to answer invasive questions about their sexual habits, are made objects of unprofessional curiosity for medical students, and are denied treatment if they don't appear to be cooperative. The Tories want fat poor people (rich fat people can do what they want!) to knuckle down and obey: they can't give the poor jobs, no matter how many statistics they massage, but they can damn well still have power over the power by threatening them with destitution if they don't play the part of the "deserving". Doctors, meanwhile, often deny vital care to trans people if they don't follow doctors' notions of what it means to be male or female (usually showing no understanding that there is any scope for gender identity beyond an old fashioned, caricatured notion of normative masculinity and femininity).

In both instances, I think we can see that the problem is paternalism. I've rarely been more glad that this year I have a book coming out on fatherhood; it might be on medieval men, but anything I can do to contribute to anti-patriarchal discourse is a good thing.